While living in Jordan as an Arabic student in 2014, I had an opportunity to organise art projects with Syrian refugees for UNHCR – an experience which opened my eyes to the magnitude of the refugee crisis confronting our world today. I began to paint the portraits of some of the refugees I had met, to show the people behind the global crisis, whose personal stories are otherwise often shrouded by statistics.

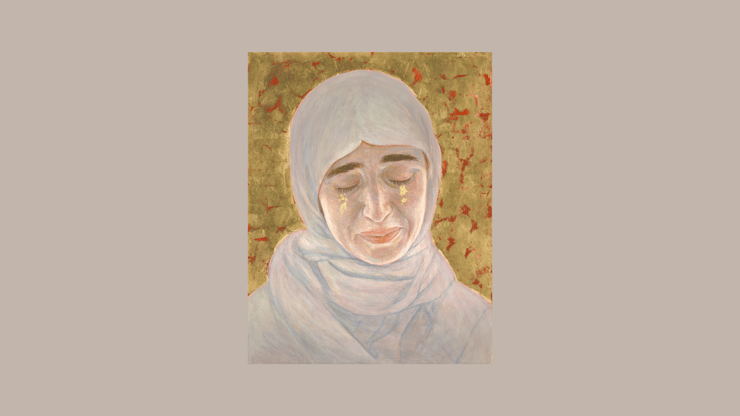

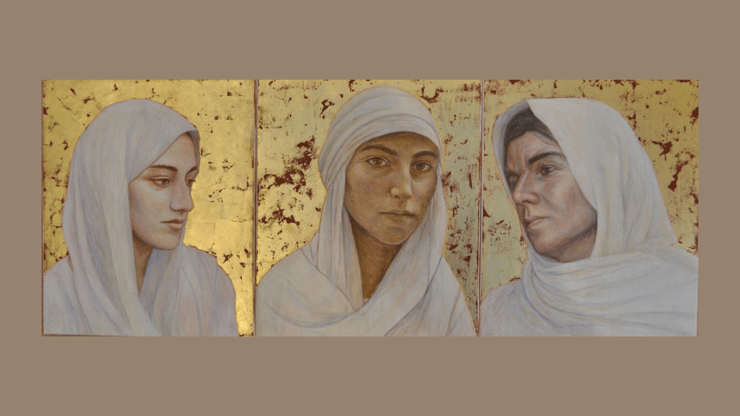

The portrait paintings are an attempt to recreate a face-to-face encounter of sorts, a reminder of the individuals at the heart of these humanitarian crises, which are so distant and at times difficult to relate to. It was to share their stories that I began painting their portraits. By facilitating processes of empathy, the creative arts enable one to understand the plight of the ‘other’ and once again to see the human being within, affirming their inherent dignity and value.

I’ve since had the privilege of organising art projects with Yezidi women who escaped ISIS captivity in Iraqi Kurdistan; Rohingya refugees in refugee camps in Bangladesh; and Christian women, survivors of sexual violence at the hands of Boko Haram or Fulani militants in Northern Nigeria. The purpose of the art projects are twofold – both therapeutic and also for advocacy - to empower the women’s voices to be heard and advocate on their behalf. Through my work as an artist it is my hope to be a voice for the voiceless and prescribe dignity to the forcibly displaced.

As a portrait painter I hope to communicate something of the beauty and sacred value of each individual in the eyes of God, regardless of race, religion or gender. Mother Teresa spoke of "seeking the face of God everywhere, everything, everyone all the time... especially in the distressing disguise of the poor". Made in the image and likeness of God, every individual is endowed with intrinsic dignity, imbued with a worth and a sacredness. How different would it be if we were to see the stranger as a bearer of the image of God and of equal value in His eyes?

The use of gold leaf for my paintings of Yezidi and Nigerian women, survivors of violence and violation, is symbolic of their sacred value and dignity regardless of what they have suffered. It is also reminiscent of icon paintings. Often tears would fall while I was painting; contemplating all that the women had endured, and their ongoing suffering. The process of painting their portraits is in many ways a form of prayer – an outpouring of lament before God – before the God who weeps and suffers alongside us.

In the recent roundtable discussion with the Rose Castle Foundation and UNHCR, I was struck by the common thread running through the sacred texts of the different religious traditions - the welcome of the stranger as the welcome of God.

This reminds us of the idea of the stranger as a gift; a blessing that enriches our lives. It is the origin of the concept of hospitality as an unconditional sacred gesture, reminding us of our shared humanity and also shared vulnerability, for today’s host may become tomorrow’s guest. This understanding of common humanity brings with it responsibility for others.

The idea of "unconditional hospitality" is grounded in notions of Biblical Hospitality. Derrida, who developed the concept of hospitality-as-ethics, affirms that "God will be first of all, as it is said, 'he who loves the stranger’". Therefore, to be turned to God means being turned to the displaced who have no standing before the law. For the God "who loves the stranger" makes His face shine upon these very people.

This bears a distinct contrast to the hostile rhetoric of the Nationality and Borders Bill, currently at Committee Stage in Parliament. (In)hospitality seems at the heart of political decision-making regarding whether or how to welcome the Other; the Bill effectively criminalises those exercising their right to seek asylum in the UK. We must appeal for the dignified and humane treatment of our sisters and brothers fleeing war, persecution and human rights abuses, who arrive here seeking sanctuary and a new beginning.

At the root of so much conflict and misunderstanding is our inability, or refusal, to genuinely see the full humanity of another individual. The practice of hospitality is to acknowledge the intrinsic value and dignity of the Other, as one in whom the image of God dwells.

The philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas observes that, "in the eyes that look at me", there shines "the whole of humanity". To see humanity in the other: To see the other's humanity. What does this ask of me? What do we refuse to see: to what do we close our eyes? How much reality of the world, of humanity, can we bear to face?

The work of Lévinas has enriched my approach to portrait painting and the art workshops with migratory communities. He spoke of the encounter of the face of the other as the encounter with the "Infinite", and therefore of infinite responsibility for the Other. Lévinas sought to identify what is ‘sacred’ about responsibility for the other, affirming the inherent dignity and value of each and every life. This prompts us to seek to understand the situation and experience of others and to overcome violence and division. Such empathy and solidarity has the potential to be transformative.

For, in the words of Hannah Arendt, "Openness to others […] is the precondition for ‘humanity’ in every sense of this word".